Supervised Classification: An Introduction and Preprocessing

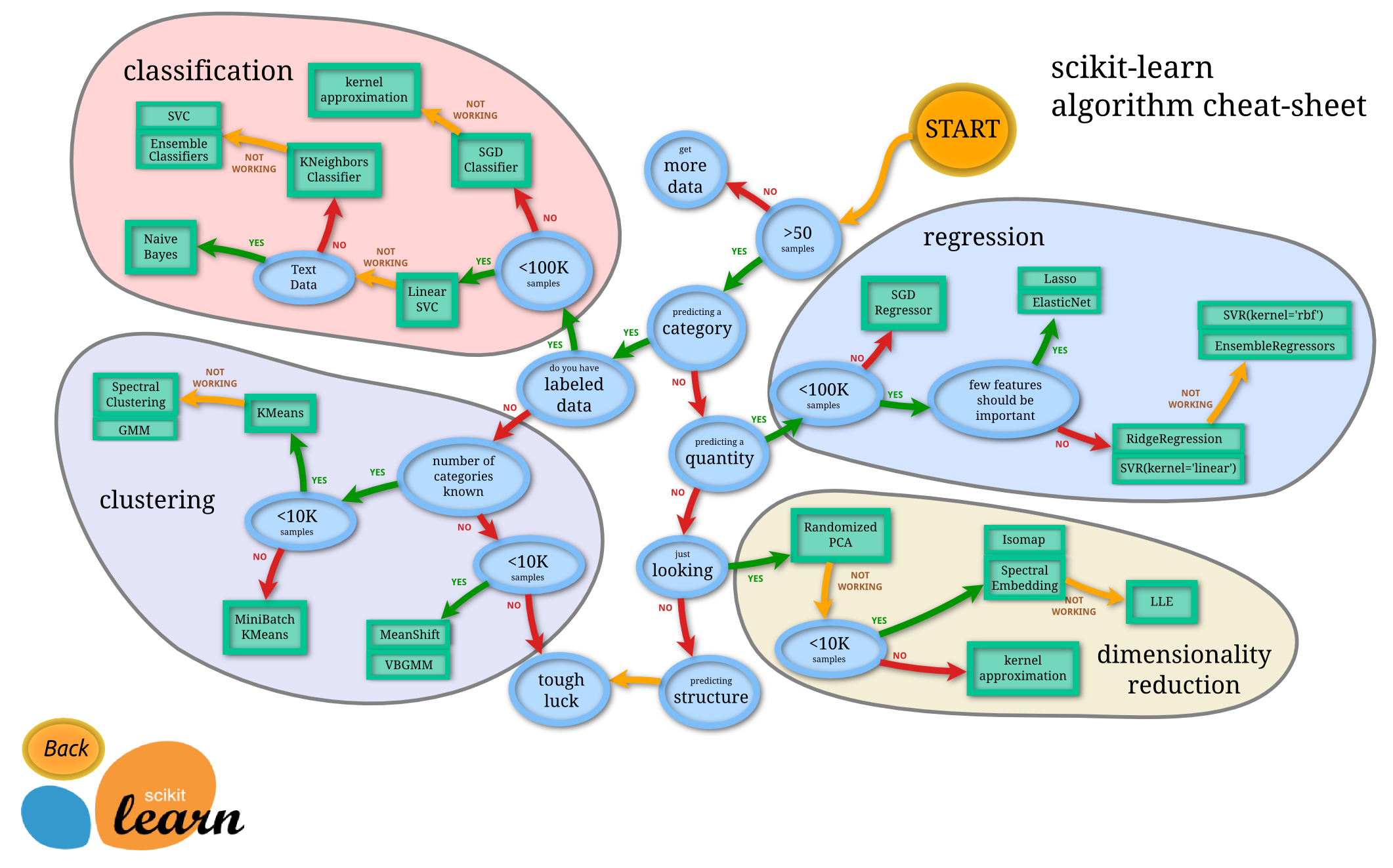

This is the initial installment of my new series as a guide to supervised classification. If you’ve got a labeled training set with multiple classes we’re going to figure out how to predict those classes. For these tutorials we will be using scikit-learn and so we will be loosely following their algorithm cheat-sheet, of course focusing on the classification quadrant. The difference is that this won’t just be a link to documentation, I’ll briefly introduce the mathematical basis of each classifier and focus on the practical usage of each algorithm. Along the way we’ll also learn some preprocessing, data cleaning, data imputation, and things to look for when training a classifier. For this post I want to briefly introduce some preprocessing steps that will come in handy which I’ll reference in later posts.

Data preprocessing and cleaning can often be the most challenging part of a problem. I could spend an entire series on these techniques (and maybe later I will), but for now let’s make sure we’re all on the same page with the basics. The most common problem that I always run into is missing or incorrect data and class imbalance. The first step I always take is to look at the reliability of each feature individually as this can inform how much data cleaning is needed, perhaps the features you’re interested in don’t need any cleaning at all! Don’t count on it… So in this post I want to cover methods to deal with:

- Missing Data

- Class imbalance

- Getting zero mean and unit variance features

- One-Hot Encoding

- Text Label Encoding

- Data visualization

Taking your time on these steps and LOOKING AT YOUR DATA along the way will greatly improve your results. Did you notice that LOOK AT YOUR DATA is capitalized? That’s because it is very important. Before we get started make sure you’re set up for doing data science, you can follow my getting started guide and how I configure my environment here.

For these tutorials we will be using the titanic dataset from seaborn. You can load it with:

import pandas as pd

titanic = pd.read_csv('https://raw.githubusercontent.com/mwaskom/seaborn-data/master/titanic.csv')Missing Data

You can quickly take a look at the data with titanic.head(), titanic.sample(n=5) or titanic.describe(). We can also use titanic.shape to see that we have 891 rows and 15 columns. You can quickly see that even in the first few rows there are a few NaN values. Let’s see how those are distributed:

>>> titanic.isnull().sum()

survived 0

pclass 0

sex 0

age 177

sibsp 0

parch 0

fare 0

embarked 2

class 0

who 0

adult_male 0

deck 688

embark_town 2

alive 0

alone 0

dtype: int64So we see that we’re missing some age values, a couple passengers are missing their embarkation information and most records do not have a deck value. Let’s replace the missing ages with a median age.

titanic['age'].fillna(titanic['age'].median(), inplace=True)fillna is a great function which can take a single value as we’ve used here as well as a Series or list of values to fill. These will allow you to implement any sort of imputation you may like and there are quite a few of them. For most cases mean or median substitution is sufficient as a first attempt in the case that not too many records are missing data. When too many records are missing data, such as deck above, we have two options, attempt imputation or ignore the feature. For brevity of this cursory explanation we’re going to ignore deck. For now…

Class imbalance

If we look at our classes which we are trying to predict we will see that there is some imbalance, more passengers did not survive on the titanic.

>>> titanic.survived.value_counts()

0 549

1 342

Name: survived, dtype: int64There are many ways to deal with class imbalance but the simplest is to upsample the underrepresented class or downsample the overrepresented class. Typically this issue only becomes a problem if the class imbalance is very large (larger than it is here) in which case it is usually best to downsample as long as you have enough data. Now if you don’t have enough data to downsample it’s very likely you don’t have enough data for accurate classification but you can always try upsampling. Here I’ll demonstrate upsampling using scikit-learn’s resample:

from sklearn.utils import resample

# Separate majority and minority classes

df_majority = titanic[titanic.survived==0]

df_minority = titanic[titanic.survived==1]

# Upsample minority class

df_minority_upsampled = resample(df_minority,

replace=True, # sample with replacement

n_samples=df_majority.shape[0], # to match majority class

random_state=123) # reproducible results

# Combine majority class with upsampled minority class

df_upsampled = pd.concat([df_majority, df_minority_upsampled])

# Display new class counts

df_upsampled.survived.value_counts()

1 549

0 549

Name: survived, dtype: int64Getting zero mean and unit variance features

It is often desirable to transform features to have zero mean and unit variance to reduce scale and bias effects. This can be done easily with scikit-learn’s StandardScaler. Let’s make the titanic fares zero mean and unit variance with the following:

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

scaler = StandardScaler().fit(titanic.fare.values.astype('float').reshape(-1, 1))

titanic['fare_standard'] = scaler.transform(titanic.fare.values.reshape(-1, 1)).ravel()

titanic.describe()

fare_standard

count 8.910000e+02

mean 3.987333e-18

std 1.000562e+00Now you can see that our fares have zero mean and unit variance!

One-Hot Encoding

One hot encoding is one way to transform a categorical variable into a boolean representation of each possible category. For the titanic dataset we can use the class categorical variable as an example. This could be represented as a continuum with first class being 1 and third class being 3 or we can treat it as a categorical variable and use one-hot encoding. Pandas has a simple utility for one-hot encoding called get_dummies.

titanic = pd.concat([titanic, pd.get_dummies(titanic['class'], prefix='class')], axis=1)

titanic.head()

survived pclass sex age sibsp parch fare embarked class \

0 0 3 male 22.0 1 0 7.2500 S Third

1 1 1 female 38.0 1 0 71.2833 C First

2 1 3 female 26.0 0 0 7.9250 S Third

3 1 1 female 35.0 1 0 53.1000 S First

4 0 3 male 35.0 0 0 8.0500 S Third

who adult_male deck embark_town alive alone fare_standard \

0 man True NaN Southampton no False -0.502445

1 woman False C Cherbourg yes False 0.786845

2 woman False NaN Southampton yes True -0.488854

3 woman False C Southampton yes False 0.420730

4 man True NaN Southampton no True -0.486337

class_First class_Second class_Third

0 0 0 1

1 1 0 0

2 0 0 1

3 1 0 0

4 0 0 1We see that we now have boolean flags for each class. We could repeat this process for any other categorical variable such as sex, who and so on.

Text Label Encoding

Occasionally you’ll want to represent categories as unique integer numbers. I’ve mostly run into this case for recommendations. Although scikit-learn has sklearn.preprocessing.LabelEncoder if your data is in pandas you can use the built in categorical data type in pandas.

titanic.sex = titanic.sex.astype('category')

titanic.sex.cat.categories

Index([u'female', u'male'], dtype='object')

titanic.sex.cat.codes.head()

0 1

1 0

2 0

3 0

4 1

dtype: int8Data visualization

There is so much to cover here but I highly recommend working through this notebook which provides a great introduction to visualization of datasets.

Keep an eye out for the next installment which will cover linear support vector classifiers

Leave a Comment